Advanced Programming Course Notes

Topic 1: course intro & java basics

Methods

Examples

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

class PrimeFinder {

static boolean isPrime(int n) {

for (int x = 2; x <= (int) Math.sqrt(n); x++) {

if (n % x == 0) {

return false; // early termination

}

}

return true; // not divisible by any number <= sqrt(n)

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

if (args.length < 1) {

System.out.println("usage: java PrimeFinder <max-range>");

return;

}

int maxRange = Integer.parseInt(args[0]);

for (int i = 2; i <= maxRange; i++) {

if (isPrime(i)) {

System.out.println(i);

}

}

}

}

Write a program to out put the following patterns

1

2

3

4

5

*

**

***

****

*****

1

2

3

4

5

6

int i, j;

final int N = 5;

for (i = 1; i <= N; i++) {

for (j = 1; j <= i; j++) System.out.print('*');

System.out.println();

}

Passing by value/reference

Pass by value

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

public static void tripleValue(double x) {

x = 3 * x;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

double percent = 10;

System.out.println("Before: percent=" + percent); // 10

// When the method ends, the parameter variable x is no longer in use.

// Meanwhile percent has not been touched because only value of percent is passed.

tripleValue(percent);

System.out.println("After: percent=" + percent); // still 10

}

Pass by reference

Correct example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

public class callbyref_modify {

public static void raiseSalary(Employee x, double byPercent) {

double salary = x.getSalary();

double raise = salary * byPercent / 100;

x.setSalary(salary + raise);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

var harry = new Employee("Harry", 30000);

System.out.println("Before: salary=" + harry.getSalary()); // 30000

// the value of location address of harry is passed

// the method modifies the salary of the object of that location address

// when the method ends, x is no longer in use

// but harry continues to refer to the object whose salary was increased

raiseSalary(harry, 10);

System.out.println("After: salary=" + harry.getSalary()); //so the output is 33000

}

}

class Employee {

private String name;

private double salary;

public Employee(String n, double s) {

name = n;

salary = s;

}

public double getSalary() {

return salary;

}

public void setSalary(double newSalary) {

this.salary = newSalary;

}

}

Incorrect example

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

public class callbyref_swap {

public static void swap(Employee x, Employee y) {

Employee temp = x;

x = y;

y = temp;

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

var a = new Employee("Alice", 70000);

var b = new Employee("Bob", 60000);

System.out.println("Before: a=" + a.getName()); // Alice

System.out.println("Before: b=" + b.getName()); // Bob

// x and y are initialized with copies of the references to a and b

// the method swaps the copies, but not a and b

// when the method ends, x and y are no longer in use

// and the original variables a and b still refer to the same objects

swap(a, b);

System.out.println("After: a=" + a.getName()); // Alice

System.out.println("After: b=" + b.getName()); // Bob

}

}

class Employee {

private String name;

private double salary;

public Employee(String n, double s) {

name = n;

salary = s;

}

public String getName() {

return name;

}

}

In summary:

Java pass both primitive types and objects by value, not the variable/object itself.

This means:

- a method can use but not modify a parameter of a primitive type.

- a method can’t modify the reference of an object.

- for example: make it refer to a new object

- a method CAN modify the state of an object.

- for example: change the value of an instance variable

Class

A class:

- describes a set of objects with the same behaviour

- allows generalizing the types of variables

models data types:

- basic types, for example: int, double, etc.

- abstract data types, hence multiple levels of abstraction

Usage

- Definition: defines the building blocks of the class

- Instantiation: creates a physical instance in memory of the abstract data type

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

/**

* This class is used to describe a point in 2-dimensional space.

* It has three methods: add, scale, and minus.

* The add method is used to add two points together.

* The scale method is used to scale a point by a factor.

* The minus method is used to subtract two points.

*/

class Vec2d {

float x;

float y;

public Vec2d(float x, float y) {

this.x = x;

this.y = y;

}

public Vec2d add(Vec2d that) {

return new Vec2d(this.x + that.x, this.y + that.y);

}

public Vec2d scale(float alpha) {

return new Vec2d(alpha * this.x, alpha * this.y);

}

public Vec2d minus(Vec2d that) {

Vec2d temp = that.scale(-1.0f);

return this.add(temp);

}

}

Inheritance

- Models “is a” relations between types

- for example: a Square is a Rectangle

- Square = derived/inherited/subclass; Rectangle = base/super class

- Useful to reuse functionalities already implemented in the base class

- for example: area() method of Square can reuse that of Rectangle

- Base classes can implement generic functions common to all subtypes

- code to compute perimeter of a 4 sided polygon inside a class Quadrilateral

- no repetition of the capability inside each individual quadrilateral type, like rhombus, rectangle, parallelogram, etc.

- each special quadrilateral type can perform more specialized functions, such as area computation.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

public class Quadrilateral {

Vec2d a, b, c, d;

Quadrilateral(Vec2d a, Vec2d b, Vec2d c, Vec2d d) {

this.a = a;

this.b = b;

this.c = c;

this.d = d;

}

float perimeter() {

// logic to calculate the perimeter

}

}

class Parallelogram extends Quadrilateral {

Parallelogram(Vec2d a, Vec2d b, Vec2d c, Vec2d d) {

// reuse the super-class constructor

super(a, b, c, d);

}

float area() {

// logic to calculate the area

}

}

class Rectangle extends Parallelogram {

// ...and so on

}

Interfaces

- Defines a contract that every class that follows should adhere to

- ≅ a template of methods that every subclass should implement

- for example: if an app needs to enforce that each Quadrilateral object undergoes a strict type verification, say, verifying that the four points are distinct, you can specify this requirement in an interface.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

interface ConstrainedPolygon {

boolean isValid(); // each subclass MUST implement this method

}

class Parallelogram extends _4gon implements ConstrainedPolygon {

// member variables and methods go here

public boolean isValid() {

// check if this is a valid parallelogram

}

}

class Rectangle extends Parallelogram {

// member variables and methods go here

public boolean isValid() {

// override (i.e. same signature but different logic),

// as not every parallelogram is a rectangle

}

}

Abstract classes

- An abstract class can’t be instantiated; only extended

- They define types/concepts that are abstract

- do not have enough information to be realized in a stand-alone manner

- for example: a Shape is too abstract to exist on its own

- they sit at the roots of class hierarchies, hence, they have to be public

- do not have enough information to be realized in a stand-alone manner

- Used to group together classes that should have common functions of different implementations: abstract methods

- for example:

checkIfInsidefor the Shape abstract class – checking if a given point is within the shape once it’s actually defined

- for example:

- They can also contain normal methods and variables

1

2

3

4

5

public abstract class Shape {

public abstract boolean checkIfInside(Vec2d a);

// no implementation!

// all extending classes MUST implement this

}

Interfaces compares to abstract classes

- Both can’t be instantiated

- Both can inherit/extend others of their own type

- Both contain abstract methods

- Interfaces only contain abstract methods

- hence no need for the abstract keyword

- Abstract classes define a common type, a concept

- contains implemented / non-implemented logic and variables

- inherited, creating a hierarchy of types

- Interfaces define expected behaviour

- notionally a finer type of contract

- a class can implement more than one interface

Topic 1 Lab

What you will do in this lab:

- Design and inherit classes

- Make your own abstract class and interface - Refactor classes to construct class hierarchies

Exercise 1a: Compiling

This initial exercise gives you some practice of compiling and running code from the command line.

- Open a text editor and write a short Java programme with a main method that prints Hello World.

- Save this is as a file called HelloWorld.java

- Open a command prompt

- Navigate to the folder containing the file you just created

- Compile the code using:

javac HelloWorld.java, if successful, this will create a HelloWorld.class file) - Run the code using:

java HelloWorldNote: java not javac, and no extension after the filename.

1

2

3

4

5

public class HelloWorld {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println("Hello World");

}

}

Exercise 1b: Designing classes

Write a new Java file that has a class to represent an employee. This class is to be used for staff management purposes. The class requires to:

- Be called Employee

- Have 4 instance variables: name, ID, salary, department

- Have a constructor that takes 3 parameters to match the instance variables except ID - Have a method called

editNameto modify the employee’s name. Make sure that you use appropriate variable types and visibility modifiers.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

class Employee {

private String name;

private int ID;

private double salary;

private String department;

public Employee(String n, double s, String d) {

this.name = n;

this.salary = s;

this.department = d;

numOfEmployees++;

this.ID = numOfEmployees;

}

public void editName(String newName) {

this.name = newName;

}

public double getSalary() {

return this.salary;

}

}

Exercise 1c: Static

Create a static variable within the Employee class to hold the value of the number of employees created. Each time an Employee instance is created, ID is set according to the value of this variable which is then incremented.

Next, create a static method that prints the number of unique IDs that have been assigned to employees.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

class Employee {

...

private static int numOfEmployees = 0;

public static int getIDcount() {

return numOfEmployees;

}

}

Exercise 1d: Inheritance

Design a Manager class that inherits from Employee. The subclass needs to have an additional instance variable to hold the value of a bonus (surplus to salary). The subclass also needs to have a method called calcTotalEarnings to return the total earnings of the manager as the sum of the salary and the bonus. Also, implement a new constructor that initialises a new instance using the constructor of the superclass. Satisfy yourself that you have edited the appropriate methods.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

class Manager extends Employee {

private double bonus;

public Manager(String n, double s, String d, double b) {

super(n, s, d);

this.bonus = b;

}

public double calcTotalEarnings() {

return getSalary() + bonus;

}

}

Exercise 1e: Abstract classes

Design an abstract class Person for defining a person with a name. Go back and edit your Employee class to inherit the Person abstract class.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

abstract class Person {

String name;

}

class Employee extends Person {

...

}

Exercise 1f: Interfaces

Design a new class Invoice to represent an invoice, with instance variables to hold the value of the invoice and a textual description.

Now create an interface Payable that defines a method calcPaymentAmount which returns the value to be paid for a given class the implements the new interface. Make both the Employee and Invoice classes implement this interface.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

interface Payable {

public double calcPaymentAmount();

}

class Invoice implements Payable {

double value;

String description;

public double calcPaymentAmount() {

return this.value;

}

}

class Employee extends Person implements Payable {

...

public double calcPaymentAmount() {

return this.salary;

}

}

Topic 2: object oriented programming

Overview

Aim Explain the main concepts of Object Oriented Programming.

Contents

- Definition

- Main principles

- Key Characteristics of Objects

- Constructors

- Accessor and Mutator Methods

- The final keyword

OOP?

Object-oriented programming (OOP) is a programming paradigm that focuses on objects. As the name suggests, in OOP programs, data is stored as objects. It not only defines how to store data but also specifies the logic, or methods, that can be applied to the data.

Object-oriented programming (OOP) is older than Java. Other object-oriented programming languages include Simula, Smalltalk, C++, Objective-C, Ruby, and JavaScript. It replaced procedural programming languages such as Fortran, Pascal, C, and others. In procedural programming, the focus is on procedures and algorithms, with data coming second, it means that it treats data and procedures as interconnected and inseparable entities.

Procedural compares to OOP

Procedural approaches work effectively for small-scale issues, such as renaming a collection of files or performing simple mathematical calculations.

Object-oriented programming (OOP) is more suitable for larger problems, such as developing a web browser. For instance, a web browser involves several thousand procedures, each manipulating a set of global data. In such complex scenarios, it’s more tractable to define classes, for example:, the address bar, page contents, etc. Subsequently, defining methods per class approximately 20 becomes easier. This approach facilitates easier development, debugging, and code management.

With the OOP approach, each object holds specific data and functions. In other words, an object comprises both data and related methods. The implementation of the capabilities is concealed, but the means to trigger it are exposed. A class defines how objects are created, it serves as a template, with classes being likened to cookie cutters, and objects or instances being the resulting cookies.

Example - Loan

All data properties and methods are tied to a specific instance. The class is built around the data. It has an implementation, hidden from external use. There is a no-argument constructor. A constructor with no arguments is also available. Getters and Setters are included .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

public class Loan {

private double annualInterestRate;

private int numberOfYears;

private double loanAmount;

private java.util.Date loanDate;

/** Default constructor */

public Loan() {

this(2.5, 1, 1000);

}

/** Construct a loan with specified annual interest rate, number of years and loan amount */

public Loan(double annualInterestRate, int numberOfYears, double loanAmount) {

this.annualInterestRate = annualInterestRate;

this.numberOfYears = numberOfYears;

this.loanAmount = loanAmount;

loanDate = new java.util.Date();

}

/** Return annualInterestRate */

public double getAnnualInterestRate() {

return annualInterestRate;

}

/** Set a new annualInterestRate */

public void setAnnualInterestRate(double annualInterestRate) {

this.annualInterestRate = annualInterestRate;

}

/** Return numberOfYears */

public int getNumberOfYears() {

return numberOfYears;

}

/** Set a new numberOfYears */

public void setNumberOfYears(int numberOfYears) {

this.numberOfYears = numberOfYears;

}

/** Return loanAmount */

public double getLoanAmount() {

return loanAmount;

}

/** Set a newloanAmount */

public void setLoanAmount(double loanAmount) {

this.loanAmount = loanAmount;

}

/** Find monthly payment */

public double getMonthlyPayment() {

double monthlyInterestRate = annualInterestRate / 1200;

double monthlyPayment =

loanAmount

* monthlyInterestRate

/ (1 - (Math.pow(1 / (1 + monthlyInterestRate), numberOfYears * 12)));

return monthlyPayment;

}

/** Find total payment */

public double getTotalPayment() {

double totalPayment = getMonthlyPayment() * numberOfYears * 12;

return totalPayment;

}

/** Return loan date */

public java.util.Date getLoanDate() {

return loanDate;

}

}

External use is facilitated through publicly exposed methods. All data and implementation are encapsulated.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

import java.util.Scanner;

public class LoanTestClass {

/** Main method */

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Create a Scanner

Scanner input = new Scanner(System.in);

// Enter yearly interest rate

System.out.print("Enter yearly interest rate, for example, 8.25: ");

double annualInterestRate = input.nextDouble();

// Enter number of years

System.out.print("Enter number of years as an integer: ");

int numberOfYears = input.nextInt();

// Enter loan amount

System.out.print("Enter loan amount, for example, 120000.95: ");

double loanAmount = input.nextDouble();

// Create Loan object

Loan loan = new Loan(annualInterestRate, numberOfYears, loanAmount);

// Display loan date, monthly payment, and total payment

System.out.printf(

"The loan was created on %s\n" + "The monthly payment is %.2f\nThe total payment is %.2f\n",

loan.getLoanDate().toString(), loan.getMonthlyPayment(), loan.getTotalPayment());

}

}

Main object oriented principles

Inheritance

Creating relationships between data types is achieved through inheritance. A subclass inherits all the properties and methods of its superclass, enabling code reuse, reducing redundancy and inconsistent logic, and allowing for a hierarchy of types. More general classes, super classes or abstract classes, are positioned at the top of the hierarchy, while more specific classes reside lower down. Implicitly, all Java classes inherit from the “cosmic superclass” Object.

Encapsulation

Encapsulation involves combining data and behavior within a single unit, known as a class. This process protects the data by retaining the state and implementation details inside the class. The state can only change through method calls, positioning public methods as the gatekeepers. Methods avoid directly accessing instance fields in a class other than their own.

Define what data is made accessible: control how data is manipulated, an object is considered a “black box.”

Prevent data corruption and ensure reliability.

Abstraction

Abstraction separates implementation from usage, concealing implementation details, and exposes only ways to invoke it.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

class Employee {

private String name;

public String getName() {

return name;

}

}

Key to reuse: underlying implementation can change

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

class Employee {

private String firstName;

private String lastName;

public String getName() {

return firstName + " " + lastName;

}

}

The change is invisible to the remainder of the program.

Polymorphism

Objects can assume more than one form depending on the context. Methods can have identical signatures but function slightly differently.

Two forms of polymorphism exist:

- Overloading: writing methods with similar signatures but distinct parameters.

- Overriding: replacing existing methods with identical signatures.

Object characteristics

An object is an entity with 3 key characteristics

Behaviour: what can you do with it? What methods can you apply to it?State: how does it react when you apply methods?Identity: how’s it different from others like it?

How these characteristics differ

Behaviour: same for all objects of the same class.State: usually different between objects of the same class, only changes through method calls, this is encapsulation.Identity: always different between objects even if their state is the same, for example: 2 identical orders on Amazon are still distinct

Constructors

Constructors are special methods used to create new objects in Java. They’re always called using the new keyword. The name of a constructor is always the same as that of the class. A constructor has no return value and can have zero or more parameters. The constructor of the superclass, if any, must be called first using the super() keyword. A class can have multiple constructors, each with a unique signature. Java doesn’t support destructors since it automatically performs garbage collection.

Accessor and Mutator methods

An Accessor, getter, method retrieves the value of a class variable. A Mutator, setter, method modifies the value or reference of a class variable. In their simplest form, they serve these distinct purposes. However, in reality, they offer additional functionalities:

- Access control: controlling who can read and modify variables

- Validation: ensuring data consistency and integrity

- Consistency guarantees: maintaining an expected state of the object

- Error checking: detecting and handling potential issues

The benefits are significant:

- Encapsulation: hiding the internal representation, allowing the interface to remain constant

- Alternative: directly exposing class variables with no control

Visibility general rules

Constructors: by default, package-visible but commonly marked as public

Data fields: recommended to be private

Methods: can vary in visibility

- Public: if they’re part of a class’s interface

- Expected to keep the method available regardless of version changes

- Private/protected: mainly for internal use as helper methods

- Easier to change or even discontinue

Method Overloading

Method overloading occurs when multiple methods have the same name but different parameter lists. The distinction between these methods is determined at compile-time through a process called overloading resolution, during which the compiler identifies the most suitable method based on the number and types of the provided parameters.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

public class MethodOverloading {

/** Main method */

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Invoke the compare method with int parameters

System.out.println("compare(3,4) is " + compare(3, 4));

// Invoke the compare method with the double parameters

System.out.println("compare(3.0,4.0) is " + compare(3.0, 4.0));

// Invoke the compare method with three double parameters

System.out.println("compare(2.5,5.4,10.4) is " + compare(2.5, 5.4, 10.4));

}

/** Return the larger of two int values */

public static int compare(int num1, int num2) {

if (num1 > num2) return num1;

else return num2;

}

/** Return the smaller of two double values */

public static double compare(double num1, double num2) {

if (num1 < num2) return num1;

else return num2;

}

/** Return the minimum among three double values */

public static double compare(double num1, double num2, double num3) {

return compare(compare(num1, num2), num3);

}

}

A common example is constructor overloading:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

public class Pet {

protected String name;

protected int age;

public Pet (String name, int age) {

this.name = name;

this.age = age;

}

public Pet (String name) {

this(name, 0);

}

}

Method overriding

Method overriding occurs when a method in a child class has the same name, identical parameters, and the same return type as a method in the parent class. This distinction is determined at runtime based on the object’s type that invokes the method.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

class Employee {

private String name;

private double salary;

private String department;

public Employee (String name, double salary, String department) {

this.name = name;

this.salary = salary;

this.department = department;

}

public void setName (String name) {

this.name = name;

}

public double getSalary () {

return salary;

}

}

class Manager extends Employee {

private double bonus;

public Manager (String name, double salary, String department, double bonus) {

super(name, salary, department);

this.bonus = bonus;

}

public double getSalary () {

return super.getSalary() + bonus;

}

}

Polymorphic object variables

A variable of type X can refer to an object of class X or its subclasses.

1

2

3

Manager boss = new Manager("John", 50000, "Sales", 5000);

Employee[] staff = new Employee[3];

staff[0] = boss;

The variables staff[0] and boss refer to the same object, but staff[0] is considered to be only an Employee object by the compiler. So:

1

2

boss.setBonus(10000); // OK

staff[0].setBonus(10000); // Error

setBonus isn’t a method of the Employee class. The opposite isn’t possible. You can’t assign a superclass reference to a subclass variable.

The final keyword

Use the final keyword in a class definition to indicate that it can’t be overridden.

1

public final class Executive extends Manager {}

One good reason to use the “final” keyword is that it can be used with methods and classes, preventing overriding in subclasses. This ensures that the semantics of the class or method can’t be changed in a subclass. As the superclass developer, you take full responsibility for the implementation, and no subclass should be allowed to modify it.

Topic 2 Lab

In Lab 1, we explored inheritance. This lab delves deeper into inheritance and introduces other object-oriented concepts, notably encapsulation and polymorphism.

Exercise 2a: Inheritance

- Objective: Define a class

Petthat extends the abstract classAbstractPet. Consider if any methods need definition inPet.- Question: Are there any methods that need definition in

Pet? Why or why not?

- Question: Are there any methods that need definition in

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

public abstract class AbstractPet {

protected String name;

protected int age;

public AbstractPet(String n, int a) {

name = n;

age = a;

}

public String toString() {

return name + " is aged " + age;

}

}

There’s no need to define extra methods because the parent class AbstractPet already defined them.

Exercise 2b: Constructors

- Objective: Implement two constructors for

Pet:- A constructor with two parameters.

- A constructor with one parameter, initializing the name and setting age to 0.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

public class Pet extends AbstractPet {

public Pet(String name, int age) {

super(name, age);

}

public Pet(String name) {

super(name, 0);

}

...

}

Exercise 2c: Getters and Setters

- Objective: Define getter and setter methods for the instance variables of the

Petclass.- Ensure the name is a non-empty string and the age is a positive integer through error checking in the Setters.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

public class Pet extends AbstractPet {

...

public String getName() {

return super.name;

}

public int getAge() {

return super.age;

}

public void setName(String name) {

if (name.isEmpty()) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Name cannot be empty");

}

super.name = name;

}

public void setAge(int age) {

if (age < 0) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Age cannot be negative");

}

super.age = age;

}

...

}

Exercise 2d: Method Overriding

- Objective: Create a

toStringmethod inPetto printname + " is my pet and is aged " + age.- Questions:

- Which method is this overriding?

- The

toStringmethod inAbstractPetis itself overriding another. Which is it?

- Questions:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public class Pet extends AbstractPet {

...

// Exercise 2d: this method overrides the toString method from the parent class

// AbstractPet

// AbstractPet's toString method overrides the toString method of Object

@Override

public String toString() {

return super.name + " is my pet and is aged " + super.age;

}

}

Exercise 2e: Inheritance II

- Objective: Extend the

Petclass with two new classes:CatandDog. Add suitable instance variables for breed and furColour.- Specialize

Catwith afavouriteSpotandDogwith afavouriteToy. - Add a

giveTreatmethod toDogthat printsname + " says thanks for the treat!".

- Specialize

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

67

68

69

70

71

72

73

74

75

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

85

86

87

88

89

90

/** Exercise 2e */

public class Cat extends Pet {

private String breed;

private String furColor;

private String favouriteSpot;

public Cat(String name, int age, String breed, String furColor, String favouriteSpot) {

super(name, age);

this.breed = breed;

this.furColor = furColor;

this.favouriteSpot = favouriteSpot;

}

public String getBreed() {

return breed;

}

public void setBreed(String breed) {

this.breed = breed;

}

public String getFurColor() {

return furColor;

}

public void setFurColor(String furColor) {

this.furColor = furColor;

}

public String getFavouriteSpot() {

return favouriteSpot;

}

public void setFavouriteSpot(String favouriteSpot) {

this.favouriteSpot = favouriteSpot;

}

// Exercise 2f

public String toString(String extra) {

return super.name

+ " is a "

+ this.getBreed()

+ " and enjoys sleeping on "

+ this.getFavouriteSpot()

+ extra;

}

}

/** Exercise 2e */

public class Dog extends Pet {

private String breed;

private String furColor;

private String favouriteToy;

public Dog(String name, int age, String breed, String furColor, String favouriteToy) {

super(name, age);

this.breed = breed;

this.furColor = furColor;

this.favouriteToy = favouriteToy;

}

public String getBreed() {

return breed;

}

public void setBreed(String breed) {

this.breed = breed;

}

public String getFurColor() {

return furColor;

}

public void setFurColor(String furColor) {

this.furColor = furColor;

}

public String getFavouriteToy() {

return favouriteToy;

}

public void setFavouriteToy(String favouriteToy) {

this.favouriteToy = favouriteToy;

}

public void giveTreat() {

System.out.println(super.name + " says thanks for the treat!");

}

}

Exercise 2f: Method Overloading

- Objective: In both

CatandDog, overload thetoStringmethod to include an extra parameter and an additional sentence about the pet.- Example:

"Rex is a collie and enjoys playing with a tennis ball every day."

- Example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

public class Cat extends Pet {

...

// Exercise 2f

public String toString(String extra) {

return super.name

+ " is a "

+ this.getBreed()

+ " and enjoys sleeping on "

+ this.getFavouriteSpot()

+ extra;

}

}

public class Dog extends Pet {

...

// Exercise 2f

public String toString(String extra) {

return super.name

+ " is a "

+ this.getBreed()

+ " and enjoys playing with "

+ this.getFavouriteToy()

+ extra;

}

}

Exercise 2g: Testing

- Objective: Build a

PetTestclass to test the defined classes.- Create a

Petarray to hold objects of typesPet,Cat, andDog, instantiated with suitable values. - Invoke

toStringon each array element and discuss which variants of the method are called and why. - Pick an array element holding a

Doginstance and invokeprovideTreaton it. Discuss the outcome.

- Create a

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

/**

* Exercise 2g: Cat's toString calls the cat's toString method, because it is passed with an extra string that is only defined in the Cat class. Without the extra string, it will invoke the toString method of the parent class Pet. The same goes for Dog.

*/

public class PetTest {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Pet[] pets = new Pet[5];

pets[0] = new Dog("Fido", 5, "Labrador", "Black", "Ball");

pets[1] = new Cat("Mittens", 3, "Persian", "White", "The couch");

pets[2] = new Dog("Rex", 1, "German Shepherd", "Brown", "Stick");

pets[3] = new Cat("Snowball", 2, "Siamese", "White", "The bed");

pets[4] = new Pet("Yoyo", 2);

for (Pet p : pets) {

if (p instanceof Dog) {

System.out.println(((Dog) p).toString(" every day"));

((Dog) p).giveTreat();

} else if (p instanceof Cat) {

System.out.println(((Cat) p).toString(" every day"));

} else {

System.out.println(p);

}

}

}

}

Output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

Fido is a Labrador and enjoys playing with Ball every day

Fido says thanks for the treat!

Mittens is a Persian and enjoys sleeping on The couch every day

Rex is a German Shepherd and enjoys playing with Stick every day

Rex says thanks for the treat!

Snowball is a Siamese and enjoys sleeping on The bed every day

Yoyo is my pet and is aged 2

Topic 3: design patterns

Overview

Aim

Introduce some high-level design considerations that help create flexible designs that are easy to maintain and can cope with change

Contents

- Design Principles: Aggregation / Composition

- Design Patterns

- Composite

- Decorator

- Observer

Design principles

As your architectural design grows:

- relationships multiply

- relationships becomes more complicated

- classes diversify with more corner cases

- code evolves.

Therefore, OO principles like inheritance, polymorphism, etc. no longer suffice:

- code reuse becomes more challenging

- code can be duplicated with minimal differences

- changes could be difficult to manage.

Code maintenance deteriorates as design grows / changes which inevitably happen.

Class design

Once you have an initial OO design, you should aim to achieve:

Cohesion: a class describes a single concept and its methods logically fit to support a coherent purpose or high-level responsibility.Clarity: easy-to-explain classes, methods, and variables.Consistency: naming convention, informative naming, overload methods of similar operations, follow standard practice, for example: define a no-arg constructor.Access: use encapsulation and Getters and Setters where suitable.Appropriate member declaration: dependent on specific instance, or shared by all static instances.Inheritance: “is a” relationship, as opposed to “has a”.

Aggregation

The aggregation, sometimes composition, design principle

- separate the parts that vary from those that don’t / definitely won’t

- define contracts

- develop code to use contracts to integrate the variable parts

Result

- classes have a one-way form of association rather than inheriting

- “has a” relationship is added dynamically where&when needed

- behaviour can be changed at runtime

- implementation is independent from design

- maximising code reuse and separation of concerns

Example:

A web server can compress images in different ways, having one compression method is restricting. Instead, create the interface

1

2

3

public interface CompressAlgorithm {

byte [] compress(byte[]);

}

That’s implemented by classes such as:

1

2

3

4

5

public class ZlibCompression impletements CompressAlgorithm {

public byte [] compress(byte[]) {

// code to compress using the zlib structure

}

}

And instantiate from this or other classes that implement the CompressAlgorithm interface “has a relationship”. This way, you are changing behaviour at runtime rather than inheriting only one behaviour at design time.

Design patterns

The composite pattern

In some applications there’s a need to perform the same operation on objects or groups of objects such as collections of objects to store state: array, hash table, etc. The composite pattern allows you to compose objects into hierarchies, and treat individual objects or compositions of them in a uniform manner.

For example:

- online store: applying discount rates on individual or multi-pack items

- e-commerce: aggregating nested inventories from providers using different systems

- file system: computing the size of files and folders

- GUI: all components from the top-level down perform the same operation, for example: click

Main elements:

Component

Component is the highest level of abstraction, typically an interface. It defines all methods that are able to be invoked on objects / groups of objects.

- doOperation: key logic

- add, remove: group management

- getChildren, getParent: hierarchy traverse

1

2

3

public interface ShopComponent {

public Double compPrice(Double discount);

}

Leaf

Leaf is a class for individual objects in the system that implements the operation and hierarchy traversal methods defined in the component.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

public class ShopLeaf implements ShopComponent {

private Double basePrice;

private Boolean canBeDiscounted;

private String name;

// Constructor - set the properties of the item

public ShopLeaf(Double base, Boolean disc, String n) {

basePrice = base;

canBeDiscounted = disc;

name = n;

}

// Comp price - only discounts if discounting is allowed

public Double compPrice(Double discount) {

if (canBeDiscounted) {

return basePrice * (1.0 - (discount / 100.0));

} else {

return basePrice;

}

}

// Nice display

public String toString() {

return name;

}

}

Composite

Composite is a class for groups of objects. It implements everything defined in the Component interface, including group management logic.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

import java.util.ArrayList;

public class ShopComposite implements ShopComponent {

// This will store the leaves

private ArrayList<ShopComponent> children;

private String name;

// Constructor - create the list and set the name

public ShopComposite(String n) {

children = new ArrayList<ShopComponent>();

name = n;

}

// Composites normally delegate the methods to the leaves

public Double compPrice(Double discount) {

Double price = 0.0;

// arraylists can be iterated...

for (ShopComponent a : children) {

price += a.compPrice(discount);

}

return price;

}

// Add and remove just call the arraylist methods

public void add(ShopComponent a) {

children.add(a);

}

public void remove(ShopComponent a) {

children.remove(a);

}

// A nice toString method that displays the composite name

// and the children names

public String toString() {

String totalString = name;

totalString += " {";

for (ShopComponent a : children) {

// Invokes toString on children..

totalString += a + ",";

}

totalString += "} collection";

return totalString;

}

}

The decorator pattern

The Decorator Pattern adjusts the behavior of an object without modifying its code. It composes complex behaviors without changing the interface or sub classes. It’s indeed more like encapsulation.

Main elements:

Component

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

public abstract class Beverage {

String description = "Unknown Beverage";

public String getDescription() {

return description;

}

public abstract double cost();

}

Concrete Component

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

public class DarkRoast extends Beverage {

public DarkRoast() {

description = "Dark Roast Coffee";

}

public double cost() {

return .99;

}

}

public class Decaf extends Beverage {

public Decaf() {

description = "Decaf Coffee";

}

public double cost() {

return 1.05;

}

}

public class Espresso extends Beverage {

public Espresso() {

description = "Espresso";

}

public double cost() {

return 1.99;

}

}

public class HouseBlend extends Beverage {

public HouseBlend() {

description = "House Blend Coffee";

}

public double cost() {

return .89;

}

}

Decorator

1

2

3

public abstract class CondimentDecorator extends Beverage {

public abstract String getDescription();

}

Concrete Decorators

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

public class Milk extends CondimentDecorator {

Beverage beverage;

public Milk(Beverage beverage) {

this.beverage = beverage;

}

public String getDescription() {

return beverage.getDescription() + ", Milk";

}

public double cost() {

return .10 + beverage.cost();

}

}

public class Mocha extends CondimentDecorator {

Beverage beverage;

public Mocha(Beverage beverage) {

this.beverage = beverage;

}

public String getDescription() {

return beverage.getDescription() + ", Mocha";

}

public double cost() {

return .20 + beverage.cost();

}

}

public class Soy extends CondimentDecorator {

Beverage beverage;

public Soy(Beverage beverage) {

this.beverage = beverage;

}

public String getDescription() {

return beverage.getDescription() + ", Soy";

}

public double cost() {

return .15 + beverage.cost();

}

}

public class Whip extends CondimentDecorator {

Beverage beverage;

public Whip(Beverage beverage) {

this.beverage = beverage;

}

public String getDescription() {

return beverage.getDescription() + ", Whip";

}

public double cost() {

return .10 + beverage.cost();

}

}

Finally, test it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

public class StarbuzzCoffee {

public static void main(String args[]) {

Beverage beverage = new Espresso();

System.out.println(beverage.getDescription() + " $" + beverage.cost());

// Make a DarkRoast object

Beverage beverage2 = new DarkRoast();

// Wrap it with a Mocha.

beverage2 = new Mocha(beverage2);

// Wrap it in a second Mocha

beverage2 = new Mocha(beverage2);

// Wrap it in a Whip

beverage2 = new Whip(beverage2);

System.out.println(beverage2.getDescription() + " $" + beverage2.cost());

Beverage beverage3 = new HouseBlend();

beverage3 = new Soy(beverage3);

beverage3 = new Mocha(beverage3);

beverage3 = new Whip(beverage3);

System.out.println(beverage3.getDescription() + " $" + beverage3.cost());

}

}

The observer pattern

The Observer Pattern helps keep your objects up-to-date about information they care about. It’s useful when your program has a class, the Subject, containing some kind of state that might be required by various other classes. The observer ensures that they’re all updated whenever the subject is updated using a publish-subscribe approach.

The Observer Pattern is used on pretty much any event-based system, such as GUI, social networks, e-commerce transactions, etc.

Main elements:

The Subject: the class that contains, and publishes, the state

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

import java.util.ArrayList;

public class Subject {

private Double[] data;

private ArrayList<Observer> observers = new ArrayList<Observer>();

public Double[] getData() {

return data;

}

public void setData(Double[] data) {

this.data = data;

this.notifyAllObservers();

}

public void attach(Observer observer) {

observers.add(observer);

}

private void notifyAllObservers() {

for (Observer observer : observers) {

observer.notifyMe();

}

}

}

The Observer: an abstract class for objects that can subscribe to state updates

1

2

3

4

5

public abstract class Observer {

protected Subject subject;

public abstract void notifyMe();

}

Concrete Observers: any class that extends the Observer to be able to subscribe and unsubscribe to state updates

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

public class ListDataObserver extends Observer {

public ListDataObserver(Subject subject) {

this.subject = subject;

this.subject.attach(this);

}

public void notifyMe() {

Double[] data = subject.getData();

System.out.println();

System.out.println("Here's the data:");

for (int i = 0; i < data.length; i++) {

System.out.println(data[i]);

}

}

}

public class MeanDataObserver extends Observer {

public MeanDataObserver(Subject subject) {

this.subject = subject;

this.subject.attach(this);

}

public void notifyMe() {

Double[] data = subject.getData();

Double mean = 0.0;

for (int i = 0; i < data.length; i++) {

mean += data[i];

}

mean = mean / (1.0 * data.length);

System.out.println();

System.out.println("Mean: " + mean);

}

}

Finally, test it:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

public class ObserverTest {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Subject s = new Subject();

Double[] d = new Double[5];

d[0] = 1.0;

d[1] = 1.2;

d[2] = 1.4;

d[3] = 1.7;

d[4] = 2.4;

new ListDataObserver(s);

new MeanDataObserver(s);

s.setData(d);

d[3] = 3.2;

s.setData(d);

}

}

Topic 3 Lab

This lab focuses on applying design patterns to solve common software engineering problems. Specifically, we will explore the Composite and Decorator design patterns.

Exercise 3a: Composite Design Pattern

- Overview: Following the shop discount calculation example from the lecture, this exercise involves enhancing the existing implementation.

- Objective: Implement a new method

compDelivery()as declared in the updated component. Determine where this method should be implemented. When invoked, it should return 5% of the total value of the items if they’re eligible for a discount, or £0 if not. - Test Case: Utilize the provided test driver class to validate your implementation. The expected output is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

iPad Air costs 30.0 to deliver.

MacBook costs 42.5 to deliver.

Power Adaptor costs 0.0 to deliver.

Magic Keyboard costs 0.0 to deliver.

Magic Trackpad costs 0.0 to deliver.

Mac accessory pack {Power Adaptor, Magic Keyboard, Magic Trackpad,} collection costs 0.0 to deliver.

MacBook pack {MacBook, Power Adaptor, Magic Keyboard, Magic Trackpad,} collection costs 42.5 to deliver.

ShopComponent.java:

1

2

3

4

5

public interface ShopComponent {

public Double compPrice(Double discount);

public Double compDelivery();

}

ShopComposite.java:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

import java.util.ArrayList;

public class ShopComposite implements ShopComponent {

// This will store the leaves

private ArrayList<ShopComponent> children;

private String name;

// Constructor - create the list and set the name

public ShopComposite(String n) {

children = new ArrayList<ShopComponent>();

name = n;

}

// Composites normally delegate the methods to the leaves

public Double compPrice(Double discount) {

Double price = 0.0;

// arraylists can be iterated...

for (ShopComponent a : children) {

price += a.compPrice(discount);

}

return price;

}

// new method

public Double compDelivery() {

Double deliveryCharge = 0.0;

for (ShopComponent a : children) {

deliveryCharge += a.compDelivery();

}

return deliveryCharge;

}

// Add and remove just call the arraylist methods

public void add(ShopComponent a) {

children.add(a);

}

public void remove(ShopComponent a) {

children.remove(a);

}

public String toString() {

String totalString = name;

totalString += " {";

for (ShopComponent a : children) {

// Invokes toString on children..

totalString += a + ",";

}

totalString += "} collection";

return totalString;

}

}

ShopLeaf.java:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

public class ShopLeaf implements ShopComponent {

private Double basePrice;

private Boolean canBeDiscounted;

private String name;

// Constructor - set the properties of the item

public ShopLeaf(Double base, Boolean disc, String n) {

basePrice = base;

canBeDiscounted = disc;

name = n;

}

// Comp price - only discounts if discounting is allowed

public Double compPrice(Double discount) {

if (canBeDiscounted) {

return basePrice * (1.0 - (discount / 100.0));

} else {

return basePrice;

}

}

// new method

public Double compDelivery() {

if (canBeDiscounted) {

return 0.05 * basePrice;

} else {

return 0.0;

}

}

// Nice display

public String toString() {

return name;

}

}

CompositeDeliveryDriver.java:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

public class CompositeDeliveryDriver {

public static void displayDelivery(ShopComponent c) {

System.out.println(c + " costs " + c.compDelivery() + " to deliver.");

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

ShopLeaf ipad = new ShopLeaf(600.0, true, "iPad Air");

ShopLeaf laptop = new ShopLeaf(850.0, true, "MacBook");

ShopLeaf powerAdaptor = new ShopLeaf(50.0, false, "Power Adaptor");

ShopLeaf keyboard = new ShopLeaf(125.0, false, "Magic Keyboard");

ShopLeaf trackpad = new ShopLeaf(115.0, false, "Magic Trackpad");

displayDelivery(ipad);

displayDelivery(laptop);

displayDelivery(powerAdaptor);

displayDelivery(keyboard);

displayDelivery(trackpad);

ShopComposite accessoryPack = new ShopComposite("Mac accessory pack");

accessoryPack.add(powerAdaptor);

accessoryPack.add(keyboard);

accessoryPack.add(trackpad);

displayDelivery(accessoryPack);

ShopComposite laptopPack = new ShopComposite("MacBook pack");

laptopPack.add(laptop);

laptopPack.add(powerAdaptor);

laptopPack.add(keyboard);

laptopPack.add(trackpad);

displayDelivery(laptopPack);

}

}

Exercise 3b: Decorator Design Pattern

- Overview: This exercise introduces the decorator pattern through a car customization scenario.

- Objective:

- Implement the

LuxuryCarclass, which hasn’t been provided. - Implement two concrete decorators:

AlloyDecoratorandCDDecorator. TheAlloyDecoratoradds an extra cost of £250, while theCDDecoratoradds £150. - Test Case: Verify your solution using the provided driver class. The correct output should be:

1

2

3

4

5

Polo costs 10000.0 and is a basic car

GolfSport costs 10250.0 and is a basic car + Alloys

GolfBeats costs 10150.0 and is a basic car + CD Player

SuperGolf costs 10400.0 and is a basic car + Alloys + CD Player

BMW costs 50150.0 and is a shinier, faster car than the basic one + CD Player

Car.java and LuxuryCar.java:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

public abstract class Car {

public abstract Double getPrice();

public abstract String getDescription();

}

public class LuxuryCar extends Car {

public Double getPrice() {

return 50000.0;

}

public String getDescription() {

return "a shinier, faster car than the basic one";

}

}

CarDecorator.java and AlloyDecorator.java and CDDecorator.java:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

public abstract class CarDecorator extends Car {

protected Car decoratedCar;

public CarDecorator(Car decoratedCar) {

this.decoratedCar = decoratedCar;

}

public Double getPrice() {

return decoratedCar.getPrice();

}

public String getDescription() {

return decoratedCar.getDescription();

}

}

public class AlloyDecorator extends CarDecorator {

public AlloyDecorator(Car decoratedCar) {

super(decoratedCar); // Call the CarDecorator constructor

}

public Double getPrice() {

return super.getPrice() + 250; // Add the price of alloys

}

public String getDescription() {

return super.getDescription() + " + Alloys";

}

}

public class CDDecorator extends CarDecorator {

public CDDecorator(Car decoratedCar) {

super(decoratedCar); // Call the CarDecorator constructor

}

public Double getPrice() {

return super.getPrice() + 150; // Add the price of alloys

}

public String getDescription() {

return super.getDescription() + " + CD Player";

}

}

DecoratorTest.java:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

public class DecoratorTest {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Car base = new BasicCar();

System.out.println("Polo costs " + base.getPrice() + " and is " + base.getDescription());

Car alloys = new AlloyDecorator(new BasicCar());

System.out.println(

"GolfSport costs " + alloys.getPrice() + " and is " + alloys.getDescription());

Car cd = new CDDecorator(new BasicCar());

System.out.println("GolfBeats costs " + cd.getPrice() + " and is " + cd.getDescription());

Car all = new CDDecorator(new AlloyDecorator(new BasicCar()));

System.out.println("SuperGolf costs " + all.getPrice() + " and is " + all.getDescription());

Car cd2 = new CDDecorator(new LuxuryCar());

System.out.println("BMW costs " + cd2.getPrice() + " and is " + cd2.getDescription());

}

}

Topic 4: Containers

Overview

Aim

- Explore some of the rich libraries provided by Java Collections Framework

- Give examples of use for you to try yourself

Contents

- Collection

- Iterator

- List: ArrayList, LinkedList

- Set: HashSet, TreeSet

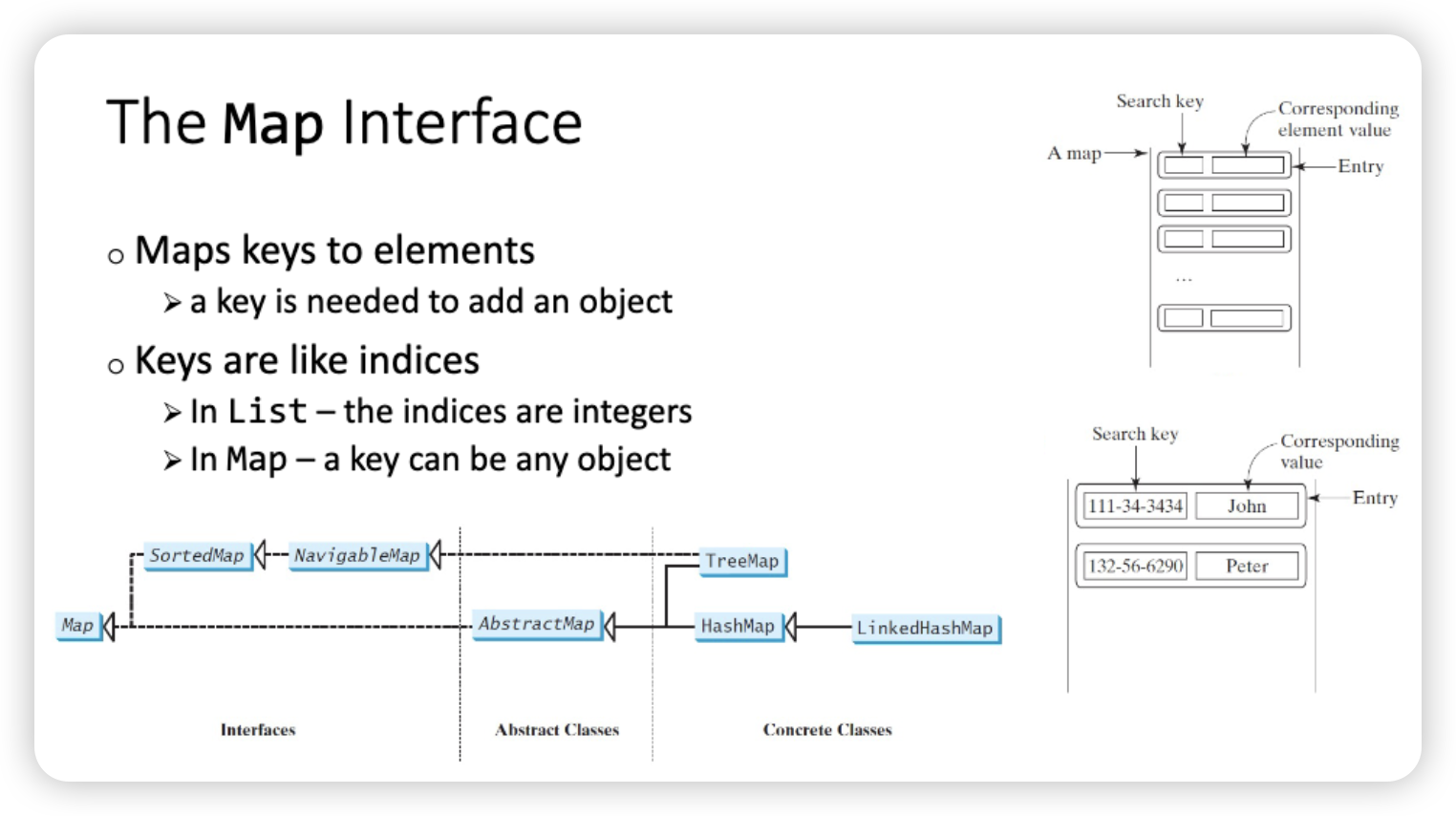

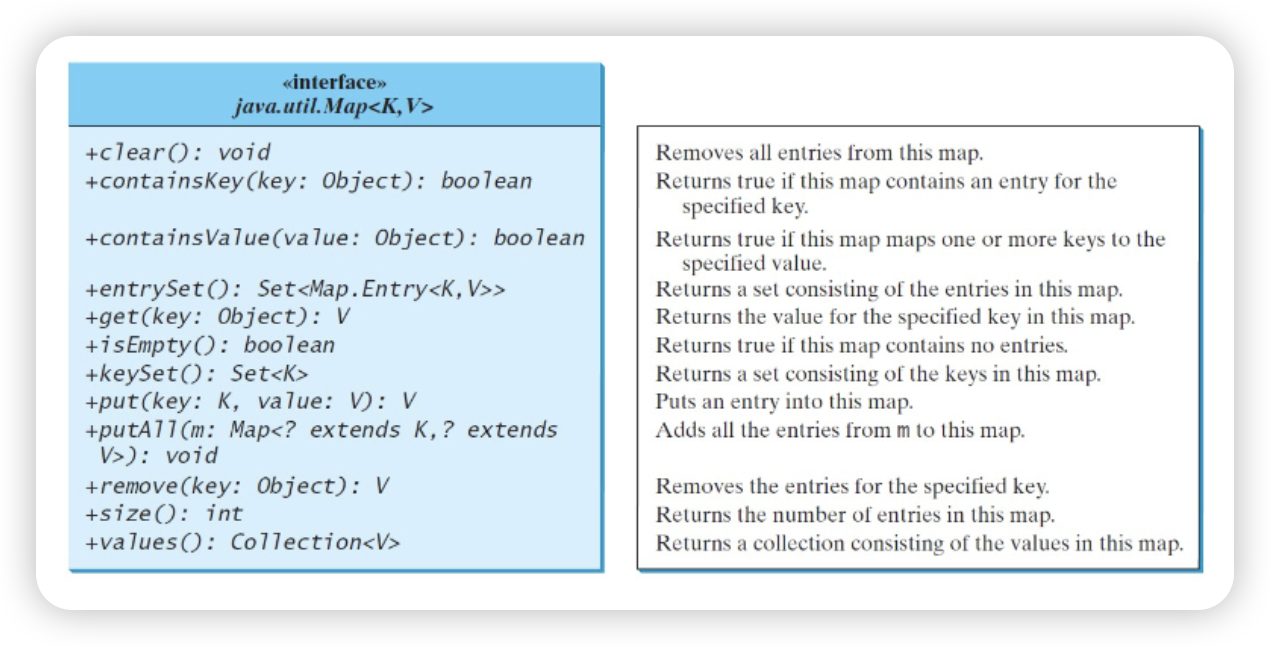

- Map: HashMap, TreeMap

Collections

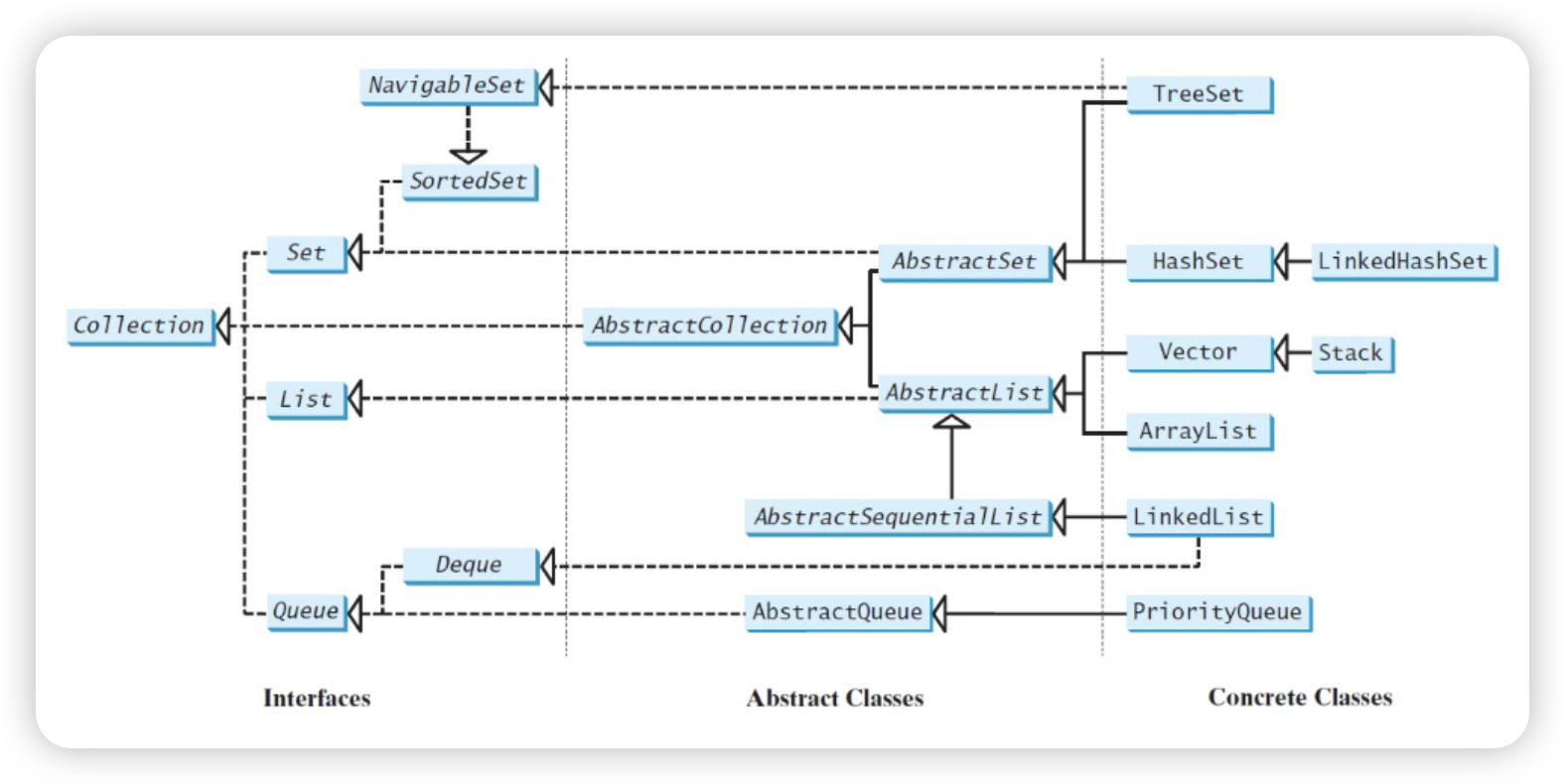

A collection is a container object that holds a group of objects. The Java Collections Framework supports three types of collections

- lists

- sets

- queues

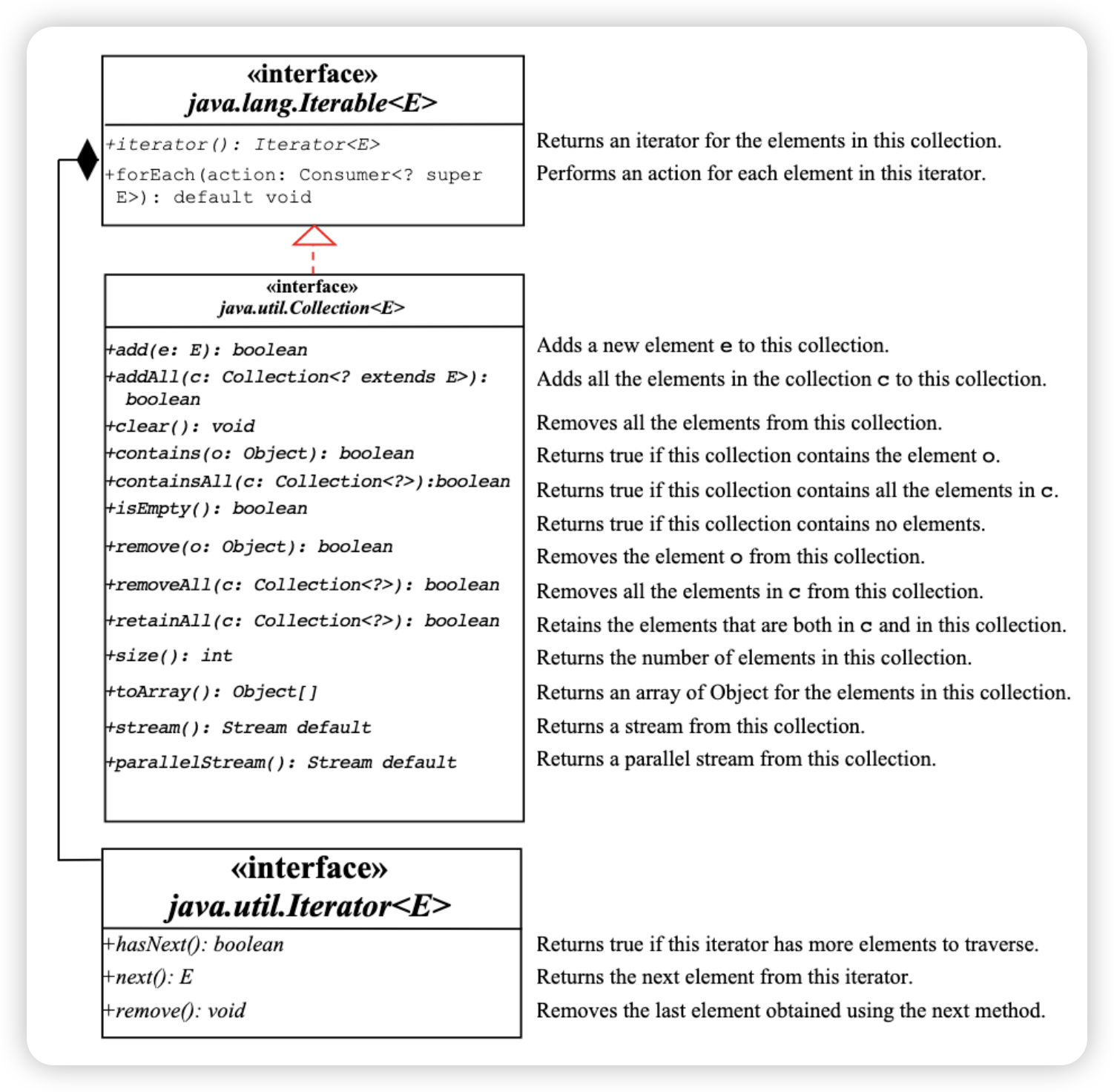

The collection interface

A common interface for manipulating a collection of objects.

see Collection

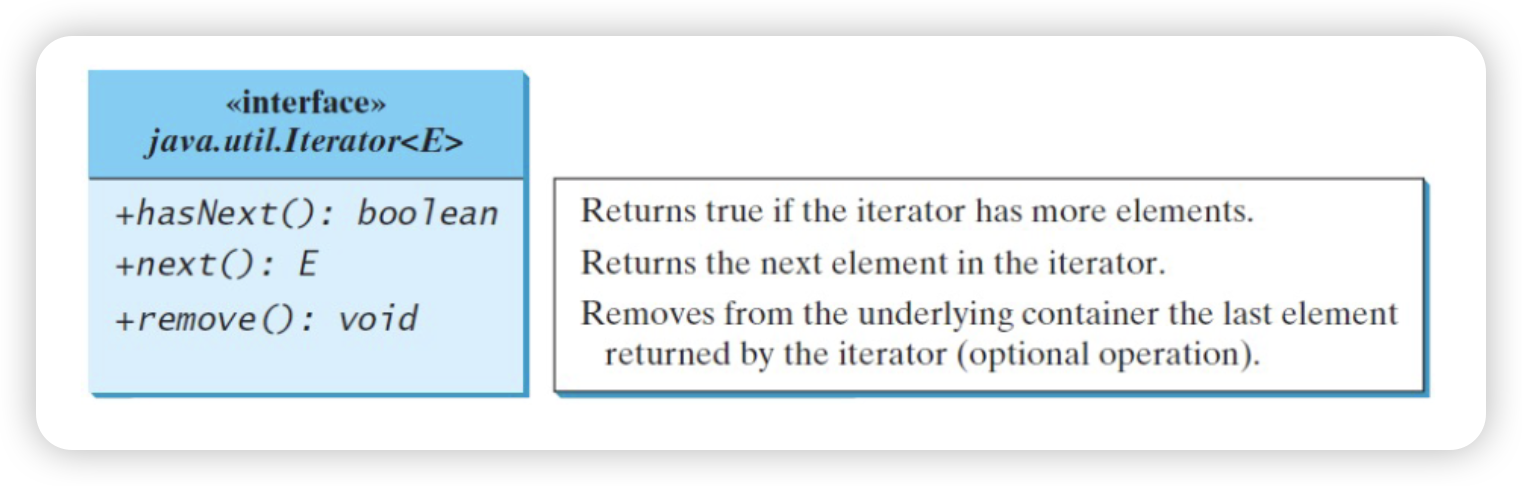

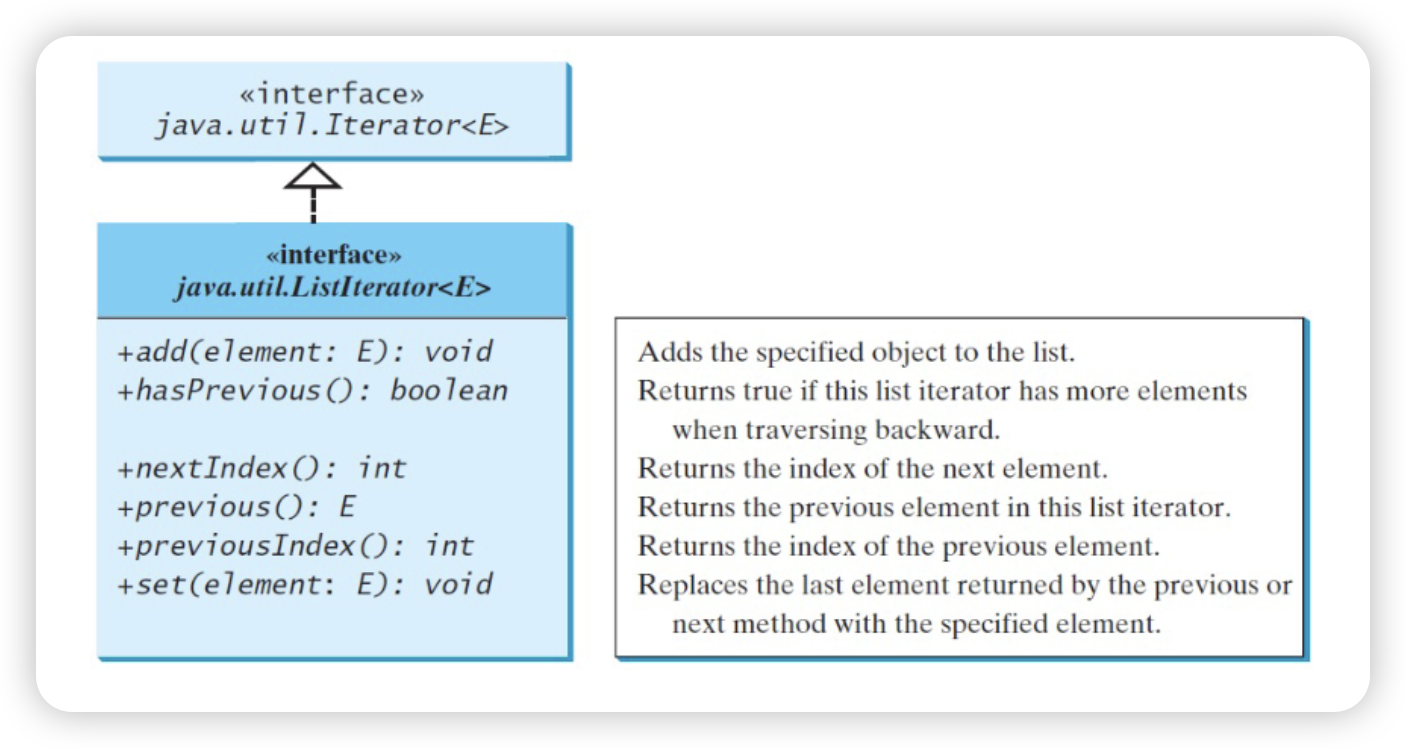

Iterator objects

Provide a uniform way for traversing elements in a container.

see Iterable

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

import java.util.*;

public class TestIterator {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Collection<String> collection = new ArrayList<>();

collection.add("New York");

collection.add("Atlanta");

collection.add("Dallas");

collection.add("Madison");

Iterator<String> iterator = collection.iterator();

while (iterator.hasNext()) {

System.out.print("-> ");

System.out.print(iterator.next().toUpperCase());

}

System.out.println();

}

}

Output:

1

-> NEW YORK-> ATLANTA-> DALLAS-> MADISON

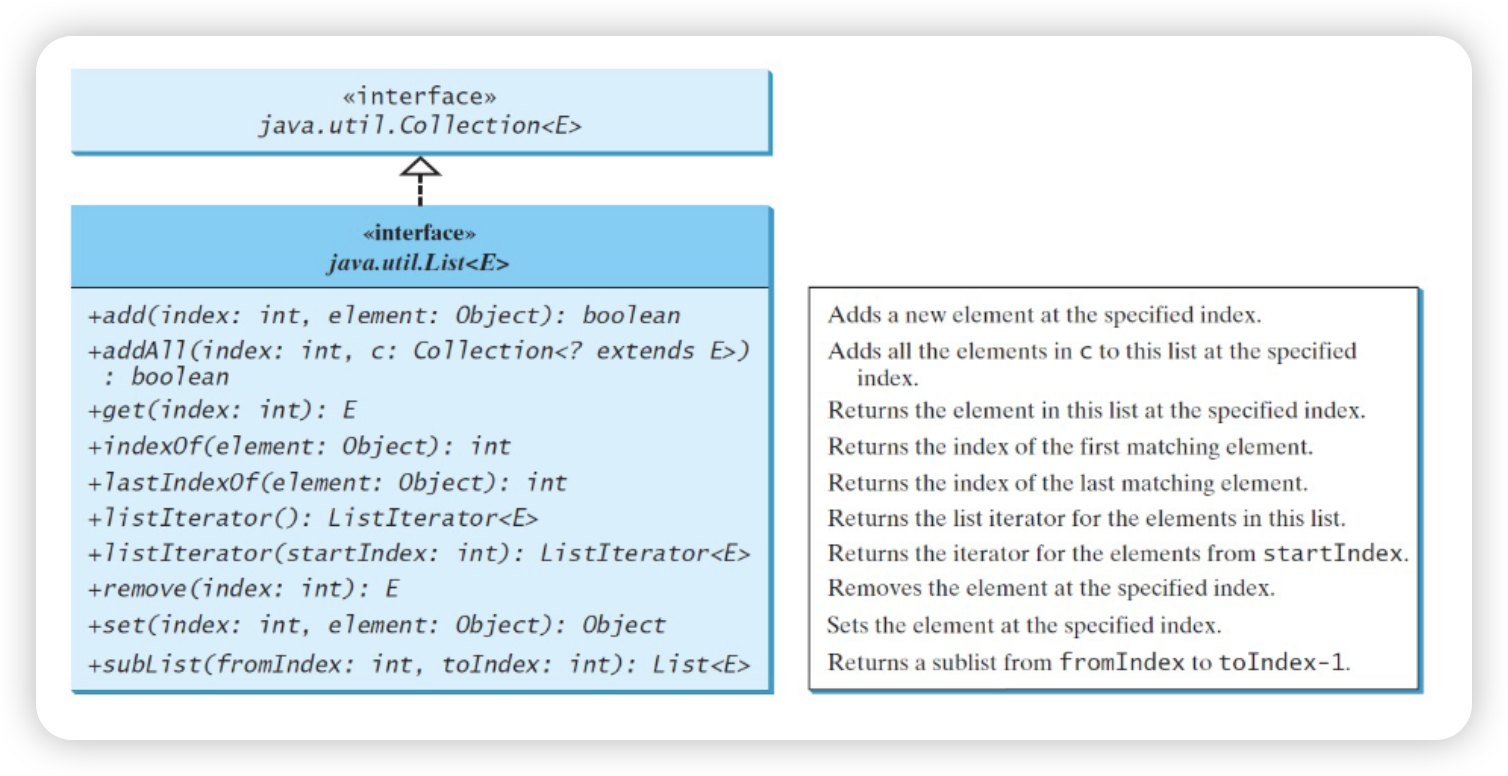

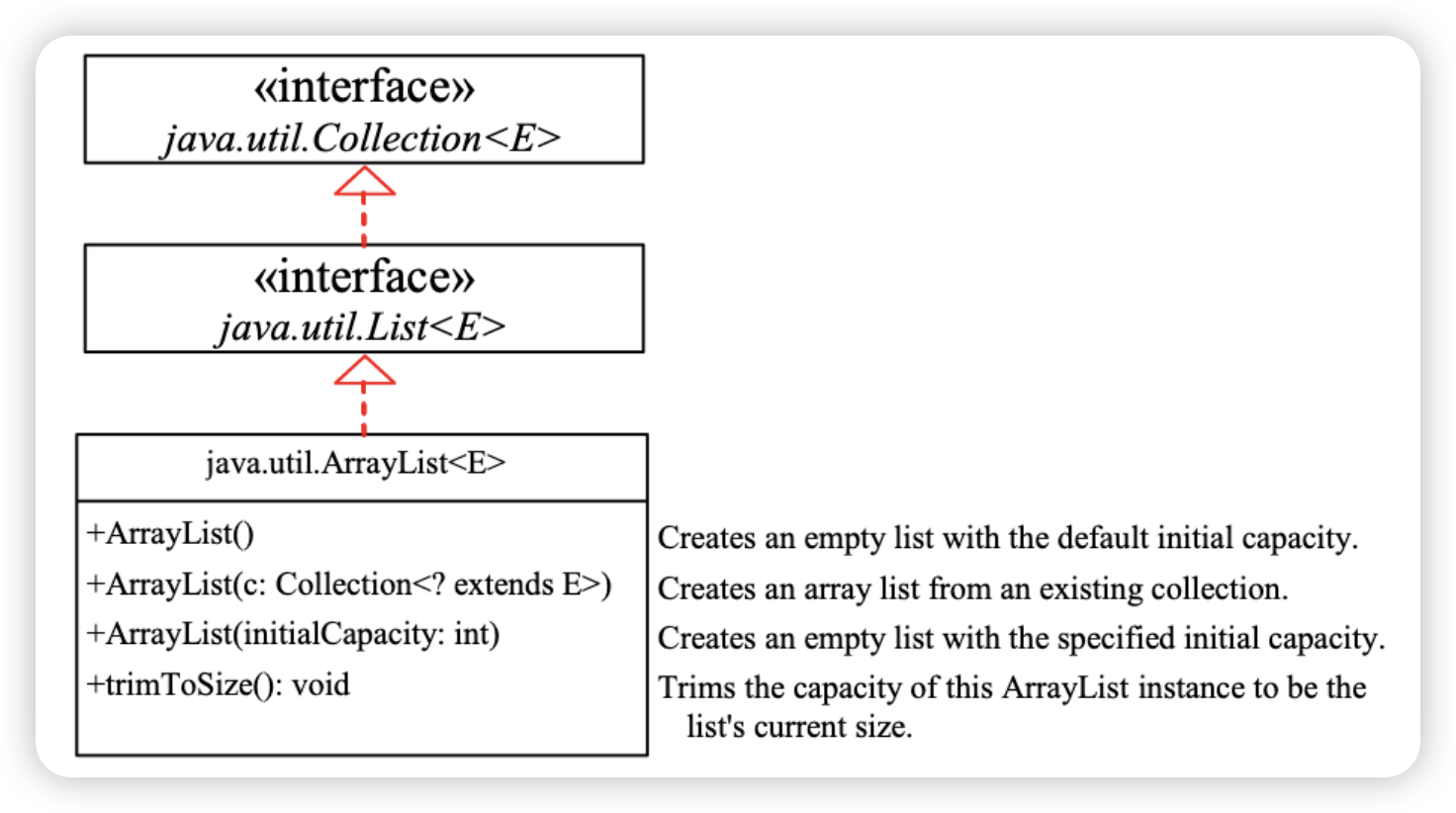

List

Stores elements in a sequential order. The user can access the elements by using their index. The user can also specify where to store an element. It’s simple to use for linear storage. You would want to linearly iterate through the container in situations such as these. Searching has a time complexity of O(n), meaning the time it takes to search is directly proportional to the size of the list. This can be improved by sorting the list, reducing the time complexity to O(log n). However, sorting becomes less effective when dealing with inputs that can grow dynamically, such as data being read from a stream, file, network, etc.

The list interface

see List

The list Iterator

Additional means of traversing list containers.

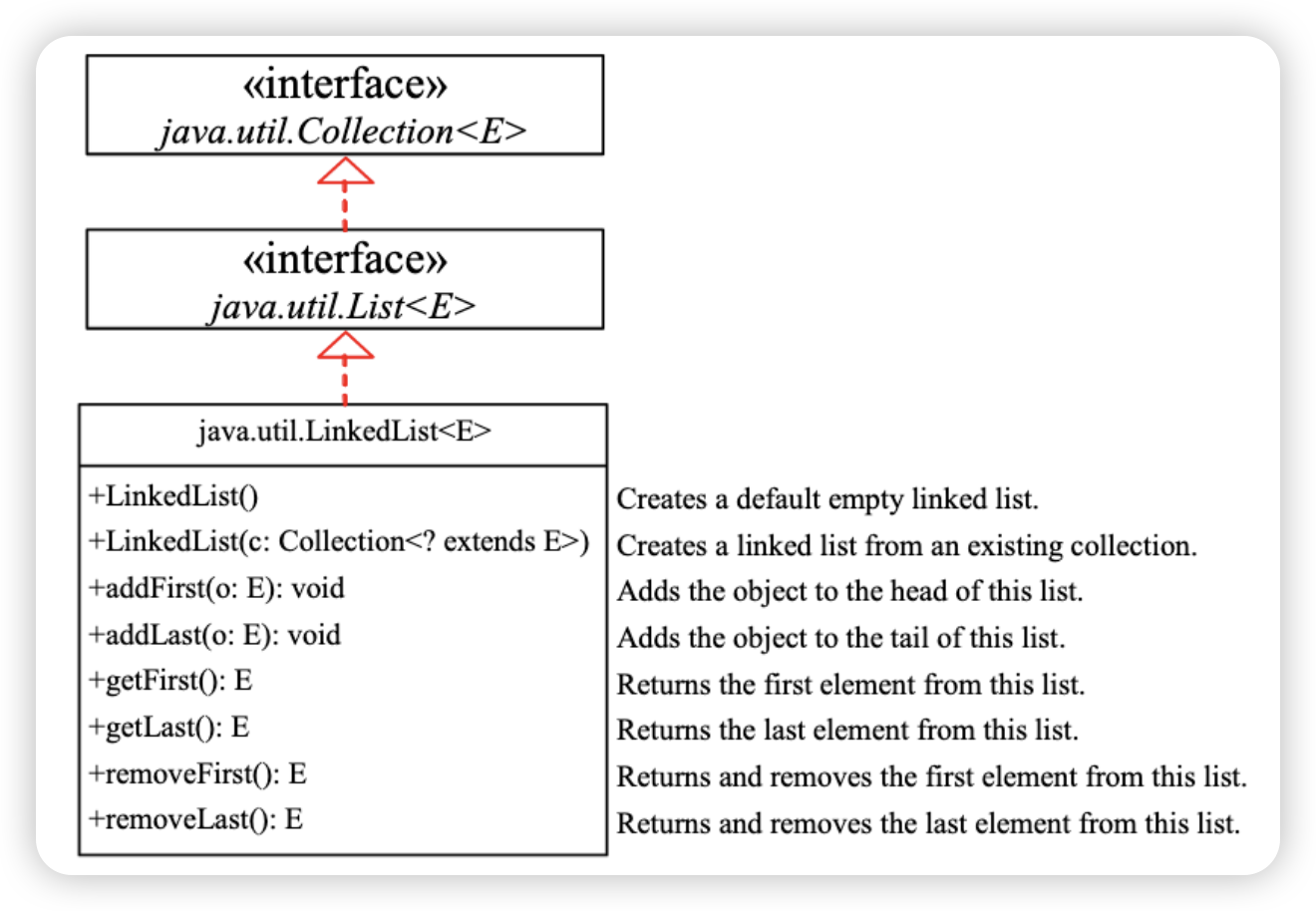

ArrayList and LinkedList

ArrayList is an option if you need to support random access through an index without inserting or removing elements from any place other than the end. For example, if reads are far more frequent than writes.

LinkedList is a better choice if you require the insertion or deletion of elements from any position in the list. In contrast, if writes are more frequent than reads.

Array is an alternative if you don’t require the insertion or deletion of elements.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

import java.util.*;

public class TestArrayAndLinkedList {

public static void main(String[] args) {

List<Integer> arrayList = new ArrayList<>();

arrayList.add(1); // 1 is autoboxed to an Integer object

arrayList.add(2);

arrayList.add(3);

arrayList.add(1);

arrayList.add(4);

arrayList.add(0, 10);

arrayList.add(3, 30);

System.out.print("A list of integers in the array list: ");

System.out.println(arrayList);

LinkedList<Object> linkedList = new LinkedList<>(arrayList);

linkedList.add(1, "red");

linkedList.removeLast();

linkedList.addFirst("green");

System.out.print("Display the linked list forward: ");

ListIterator<Object> listIterator = linkedList.listIterator();

while (listIterator.hasNext()) {

System.out.print(listIterator.next() + " ");

}

System.out.println();

System.out.print("Display the linked list backward: ");

listIterator = linkedList.listIterator(linkedList.size());

while (listIterator.hasPrevious()) {

System.out.print(listIterator.previous() + " ");

}

System.out.println();

}

}

Output:

1

2

3

A list of integers in the array list: [10, 1, 2, 30, 3, 1, 4]

Display the linked list forward: green 10 red 1 2 30 3 1

Display the linked list backward: 1 3 30 2 1 red 10 green

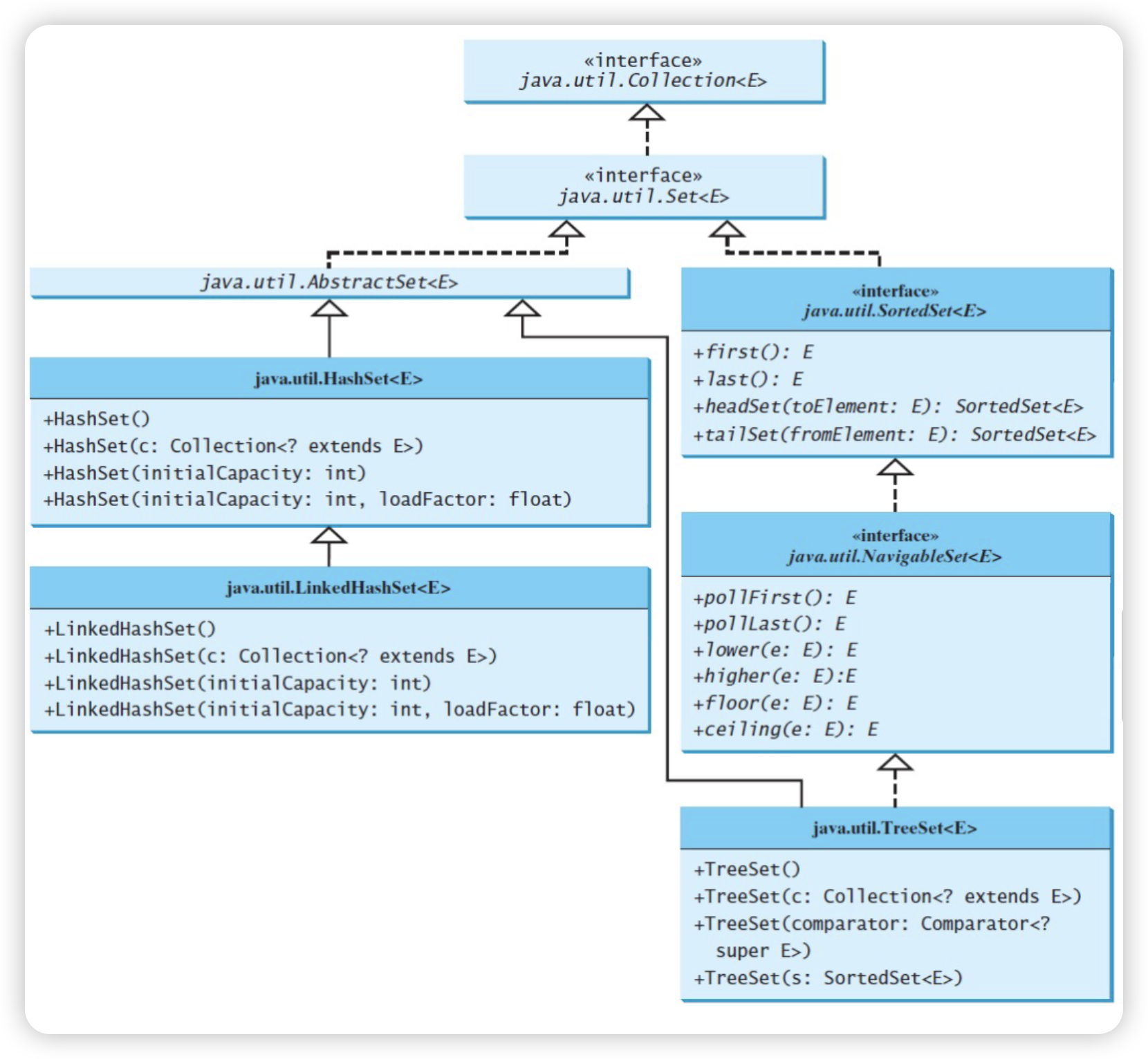

Set

Important: anything that implements Set can’t have

duplicateelements.

Useful in situations where you wish to store distinct elements. For example, checking if an element x is prime involves a simple lookup into an existing set of primes. Sets come equipped with built-in efficient search mechanisms for identifying duplicates. There are two primary implementations:

Hash Sets: An unordered collection that doesn’t maintain the order in which elements are inserted. Instead, a hash function is used to determine the existence of an element.- only needs the equality check, for which often a byte-by-byte comparison would suffice

- you must override

equals()andhashCode() - not thread-safe: if multiple threads try to modify a HashSet at the same time, then the final outcome isn’t deterministic

Hash function: A deterministic, one-way mathematical function that generates a value from a given input.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

import java.util.*;

public class TestHashSet {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Create a hash set

Set<String> set = new HashSet<>();

// Add strings to the set

set.add("Monday");

set.add("Tuesday");

set.add("Wednesday");

set.add("Friday");

set.add("Friday");

System.out.println(set);

// Display the elements in the hash set

for (String s : set) {

System.out.print(s.toUpperCase() + " ");

}

System.out.println();

// Process the elements using a forEach method

set.forEach(e -> System.out.print(e.toLowerCase() + " "));

System.out.println();

}

}

Output:

1

2

3

[Monday, Friday, Wednesday, Tuesday]

MONDAY FRIDAY WEDNESDAY TUESDAY

monday friday wednesday tuesday

Another example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

import java.util.*;

import java.io.*;

public class CountKeywords {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Scanner input = new Scanner(System.in);

System.out.print("Enter a Java source file: ");

String filename = input.nextLine();

File file = new File(filename);

if (file.exists()) {

System.out.println("The number of keywords is " + countKeywords(file));

} else {

System.out.println("File " + filename + " doesn't exist!");

}

}

public static int countKeywords(File file) throws Exception {

// Array of all Java keywords + true, false and null

String[] keywordString = {"abstract", "assert", "boolean",

"break", "byte", "case", "catch", "char", "class", "const",

"continue", "default", "do", "double", "else", "enum",

"extends", "for", "final", "finally", "float", "goto",

"if", "implements", "import", "instanceof", "int",

"interface", "long", "native", "new", "package", "private",

"protected", "public", "return", "short", "static",

"strictfp", "super", "switch", "synchronized", "this",

"throw", "throws", "transient", "try", "void", "volatile",

"while", "true", "false", "null"};

Set<String> keywordSet = new HashSet<>(Arrays.asList(keywordString));

int count = 0;

Scanner input = new Scanner(file);

while (input.hasNext()) {

String word = input.next();

if (keywordSet.contains(word))

count++;

}

return count;

}

}

TreeSet:

Implements the SortedSet interface: elements are arranged in a tree. Searching for an element can be performed in logarithmic time O(log n). Member instances must implement the Comparable interface. The container should be able to determine if a is less than or equal to b or if b is greater than a, enabling proper arrangement of elements in the tree.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

import java.util.*;

public class TestTreeSet {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Create a hash set

Set<String> set = new HashSet<>();

// Add strings to the set

set.add("London");

set.add("Paris");

set.add("New York");

set.add("San Francisco");

set.add("Beijing");

set.add("New York");

TreeSet<String> treeSet = new TreeSet<>(set);

System.out.println("Sorted tree set: " + treeSet);

// Use the methods in SortedSet interface

System.out.println("first(): " + treeSet.first());

System.out.println("last(): " + treeSet.last());

System.out.println("headSet(\"New York\"): " +

treeSet.headSet("New York"));

System.out.println("tailSet(\"New York\"): " +

treeSet.tailSet("New York"));

// Use the methods in NavigableSet interface

System.out.println("lower(\"P\"): " + treeSet.lower("P"));

System.out.println("higher(\"P\"): " + treeSet.higher("P"));

System.out.println("floor(\"P\"): " + treeSet.floor("P"));

System.out.println("ceiling(\"P\"): " + treeSet.ceiling("P"));

System.out.println("pollFirst(): " + treeSet.pollFirst());

System.out.println("pollLast(): " + treeSet.pollLast());

System.out.println("New tree set: " + treeSet);

}

}

Output:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

Sorted tree set: [Beijing, London, New York, Paris, San Francisco]

first(): Beijing

last(): San Francisco

headSet("New York"): [Beijing, London]

tailSet("New York"): [New York, Paris, San Francisco]

lower("P"): New York

higher("P"): Paris

floor("P"): New York

ceiling("P"): Paris

pollFirst(): Beijing

pollLast(): San Francisco

New tree set: [London, New York, Paris]

see NavigableSet

Comparing the Collection Concrete Classes

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

import java.util.*;

public class SetListPerformanceTest {

static final int N = 5000;

public static void main(String[] args) {

// Add numbers 0, 1, 2, ..., N - 1 to the array list

List<Integer> list = new ArrayList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < N; i++)

list.add(i);

Collections.shuffle(list); // Shuffle the array list